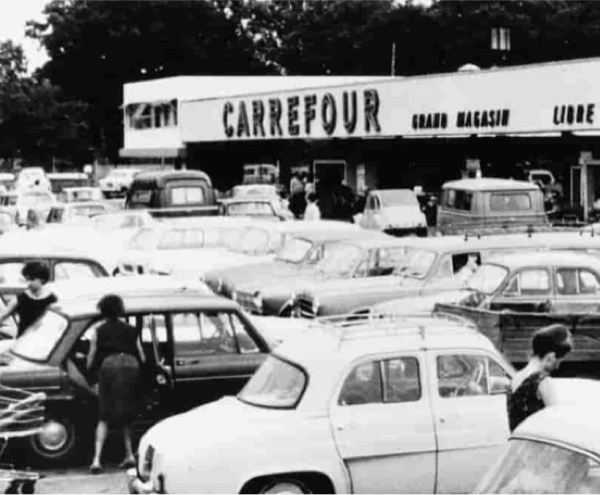

I was born in 1993 in Paris 14 and grew up in the North Suburb. In 1963, Carrefour opened the first French hypermarché in the next suburb and over 2,500 square metres. The shop advertised a low pricing policy and offered 400 free parking spots. By the end of 1999, the company Carrefour was the second biggest food distributor worldwide, with over 9,000 shops internationally. My mother loved the ‘hyper,’ as we call this place in our everyday lives, for its convenience and discounts culture. On Saturday mornings, we jumped in the car and drove to the hypermarché. It was Auchan for us. Blinding bright lights, distracting signs and announcements from floor to ceiling, maman headed towards the food aisles, sometimes stopping by the beauty section for soap and cotton pads on the way, whilst I headed to the stationery section, flipping through the Clairfontaine exercise books, or to the toys dreamland, where I fantasised at the thought of welcoming a Tamagotchi in our family.

The year I turned 18 years old, I moved to Montréal. I didn’t have a hypermarché there but there was a Metro around the corner of my flat, flashing lights 24 hours and 7 days a week. It was big enough to be called a supermarket. I shopped there for over 3 years, showing little excitement about what I would cook with the food I put in my basket, growing increasingly anxious about how I was going to afford the bill as I studied for my bachelor’s degree. It’s when I moved to London that I started to appreciate independent shops, from green and grocers to delis and fishmongers. I moved to Clapton in September 2015 and at the top of my road, there was an independent shop where you could smell moist bread first thing in the morning and buy vegetables by the unit. They also had 24-month aged Comté cheese and petit écolier biscuit, the perfect combo dinner for a rainy Tuesday. London is the first place I have mind-mapped through its local shops.

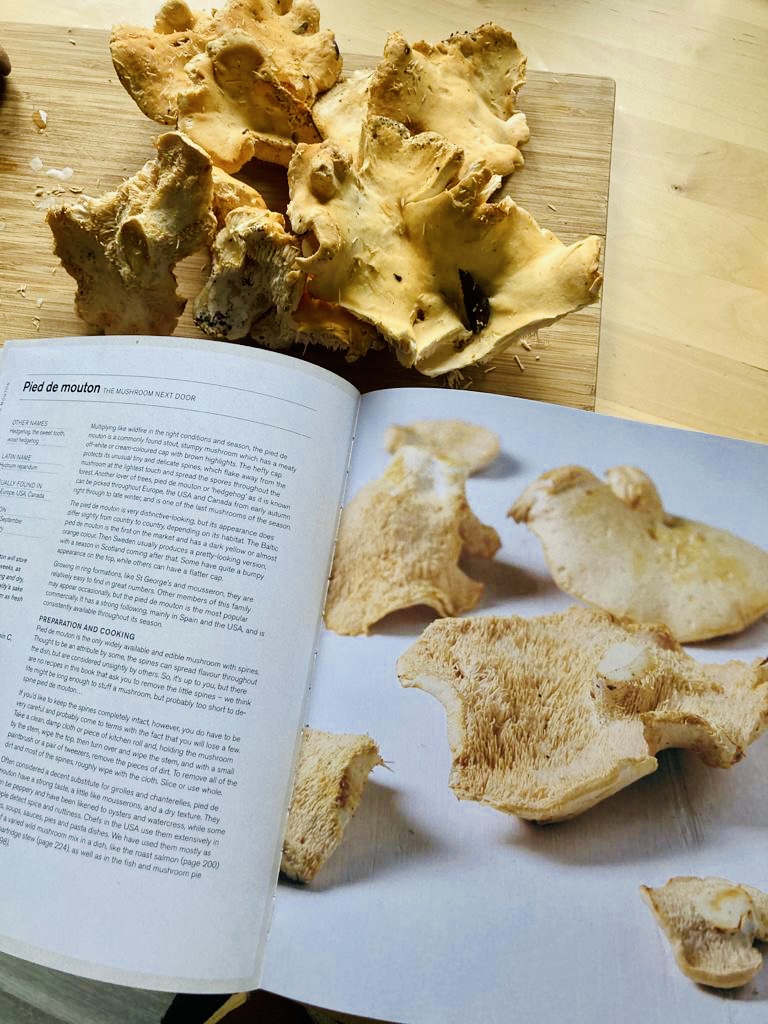

I currently live in Surrey, outside of the city for the first time. These new surroundings mean I’ve had to learn about new shops and their owners, and I’ve also discovered the British country life – and, arguably, wildlife in general. Last month, I went foraging for mushrooms for the first time. I brought back Hedgehog Fungus – also known as wood urchin, wood hedgehog and pied de mouton – this is a safe mushroom for novice foragers. They are fairly common and as long as you pick a light-coloured mushroom growing from the ground on a stem, with spines instead of gills, then it can’t be anything else. They also happen to taste deliciously nutty. On the walk back home, content with a smile on my face, I stopped to pick wild chestnuts, already plotting a mushroom ragù for dinner.

Time to start your broth: bring water to the boil and add a carrot, half an onion (in full, not chopped) and a celery.

It was the Saturday morning before our October book club, when we read M.F.K Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf. We had an animated conversation then, many of us new to the food writing genre overall, all of us in awe of Fisher and her way of inhabiting the kitchen. With her wit and pragmatism and flair for a fuel for both body and mind in each ingredient she picks, Fisher spoke to us vividly, likewise an echo chamber of our respective homes, shelters for the looming lockdown 2.0.

Turn on the oven and roast the chestnuts. You will have previously cracked their shells and removed a few splinters in your fingers. While they roast, start cutting the mushrooms in chunks, the size depending on how you like them (we go chunky).

As I read How to Cook a Wolf, I couldn’t stop picturing Fisher walking through an open air market in France, her sharp comments about the mounting hypermarché culture echoing in my head, her tricks about how to reuse cooking water getting under my skin as the walls in my flat seem to shrink.

Bring out a casserole, chop an onion and golden with a tad of olive oil. Add the chestnuts and keep stirring as you add the mushrooms. You don’t want them to get too soft but do leave them enough time to reach that nutty feel, along with the chestnuts. That’s about 3 minutes on medium heat. Tie-in together fresh thyme, rosemary, sage and a bay leaf and add to the casserole with a generous cup of tomato sauce and half of the broth. Let simmer on a low heat for as many hours as you’ve patience, slowly adding the remaining part of the broth as the mixture thickens.

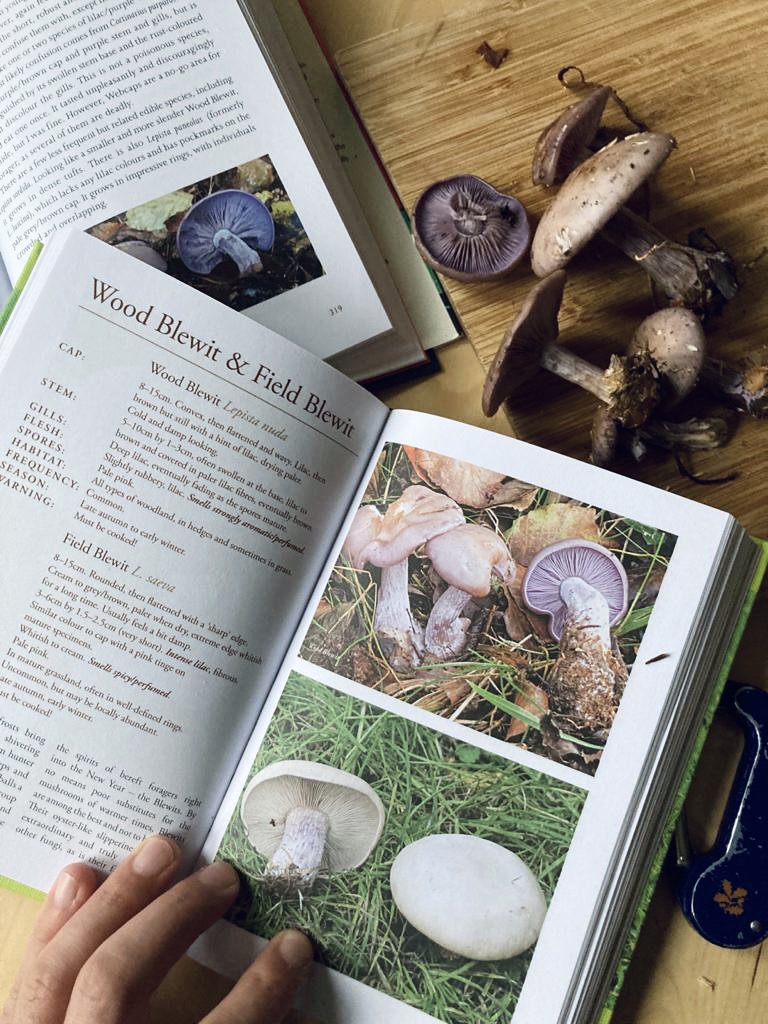

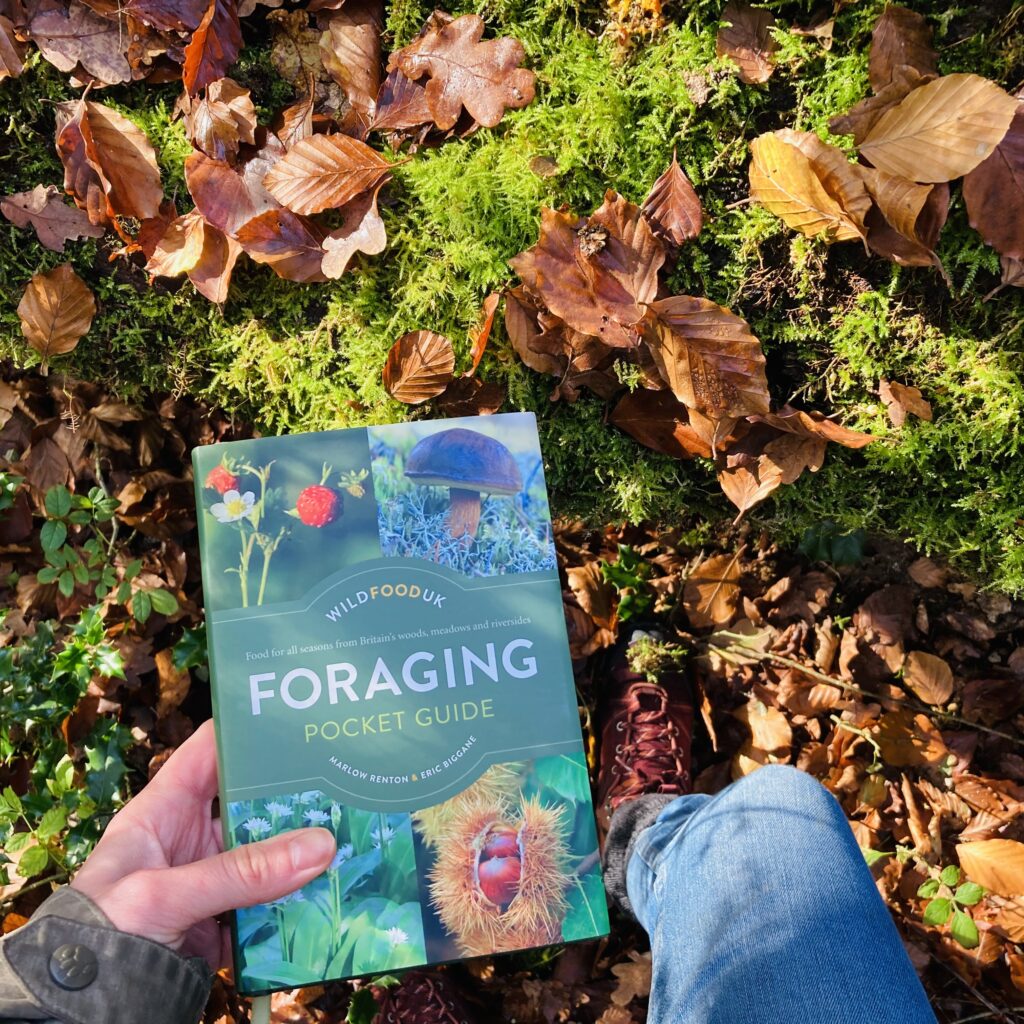

As I type this, we’re eating our ways through lockdown 2.0, and I’m back from another foraging trip. High-woollen socks on and a foraging guide in hands, my brain is stimulated by the smell and the touch of vegetables and plants and herbs before they’re paired with price and name tags on shelves.

When the ragù is near being ready or when your borborygmi take over the music in the kitchen, it’s time to prepare the polenta, cushion to a warm mushroom ragù. To serve, first spoon the soft polenta on to a wooden board and then top up with a generous amount of ragù.

What I love the most about foraging is the hunt, the excitement when I spot something from afar, the focused eyes when I flick through my foraging guide and above all, the aimless walk. No shopping list, no convincing two for one offers, no distressful ingredients list and calorie charts; the sound of cracking woods and crispy leaves, my instincts for guidance only. I most often come home empty handed. But since I started going foraging, I’ve learnt that the Bolete mushrooms have sponge like pores instead of gills and that nothing grow under a yew tree, and mushrooms like oak trees; I remembered the butter game we played with my schoolmates, with the Dandelions, ‘ et toi est-ce-que tu aimes le beurre ?’, holding the yellow flower under our chins; the fly agaric, beautiful but toxic, is named from the medieval time when the cap was broken up and left in milk to stupefy flies; all amanitas have white gills and white spores, and the amanita family is the most important to get to know since it includes some of the most poisonous fungi on the planet; most fungi reproduce when they reach maturity by releasing spores, so when picking a mushroom for identification and if it turns out to be something inedible, then it’s a good thing to throw it on the ground in the nearest environment to which it was found, so it can reproduce.

The River Cottage Handbook No.2 – Preserves by Pam Corbin – sits next to me on the kitchen table as I write this. A few days ago, I found crab apples under a tree, which I turned into my first homemade jam, wary hands as I sterilised jars and wild eyes as I thought I might never have to pick up a Bonne Maman jam jar from the hypermarché’s shelves again. I miss the buzz of the food shops but this is exciting, I tell you.

Margaux, November 2020