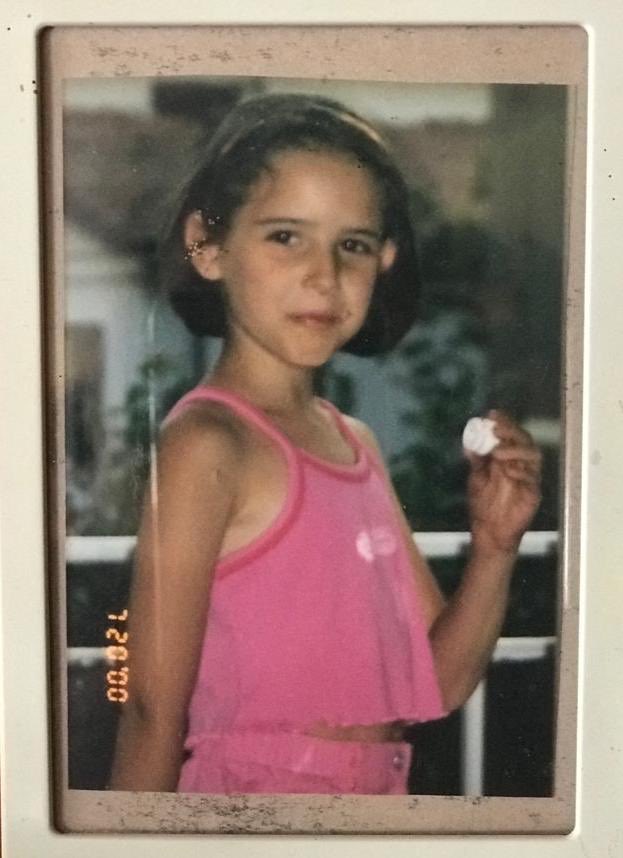

Sitting on the shelves of my parents’ house, there is a photo of me standing on my nonna’s balcony. It was shot on the 20th of July 2000, my seventh birthday. It’s warm, my hair is cut short and held back with a headband. It’s straight, a joy for my grandma who hated the curls I was born with and pulled them roughly in the bathtub whenever she washed my hair. I’m wearing a pink attire I remember loving – it’s a vest and shorts ensemble, the top leaves my belly uncovered. In my mind, I am Emma from the Spice Girls.

I’m trying to smile at the camera, but I can’t do it fully, because I’m caught eating a piece of cheese.

I never liked that photo. I loved to pose for the camera, smiling widely, and the naturalness of my captured face made me feel caught in a forbidden act. “You are always hungry,” an appellative that has followed me since childhood. It’s the first thing my family can say about me. Sometimes it hurts. I find it hard to explain that the hunger I feel is not a physical one, my stomach is not rambling, I’m not dying to eat, I’m longing to taste. It’s my brain and heart that need feeding. I need to try everything, or else I feel like I’m missing out on a key piece of knowledge. I can’t remember a time in which this hunger didn’t fuel me.

Most of my childhood food memories have been glued together through tales of others. They emerge as I dig for them, but can I call them memories or are they resurfacing only because of a present craving to remember something?

Things others said of me eating as a child – memories of sorts:

“You used to cut the tiniest bit of gorgonzola, and spread it over the tiniest crumb of bread, eat it and lick your fingers.” Zio Massimo

“I used to buy anchovies and olives only for when you came over to eat, my daughters never ate them.” Patrizia, my childhood best friend’s mother

“We would come back from the beach in Albenga to nonna Nerina’s cuttlefish in tomato sauce, and soak the sauce with fresh bread before napping.” Papà

“You didn’t like béchamel in lasagne, so I hid a small amount of it in them and tricked you to eat them.” Zia Maria Luisa

“You would escape to your room whenever I cooked tripe.” Nonna Piergiovanna

“You always wanted something more elaborate.” Mamma

Things I remember of me eating as a child:

Sitting on la Plage de l’Ilette in Antibes, under the tent dad had just built, I’d carefully peel a big chunk of pissaladière from the greasy paper of the boulangerie. I started my day with onions, anchovies and black olives, they tasted like heaven.

I insisted we went out to the restaurant at least once, and as the holiday coincided with my birthday, it often happened. I sat, composed, reading through the menu multiple times. I asked if I was allowed to taste certain things. Ever cautious me, always asking for permission, even though in my head curiosity had already decided. I’ll never forget my first snails, the tangy, chewy texture, the garlic and the parsley. I remember tasting frogs, and not being scared. Because children can be so scared of taste, but I just wasn’t. Whenever courage failed me in life, I always found it at the table.

I remember spending one week every summer at my maternal grandma’s house with my cousins, great grandma, great-aunt and uncle. We would wake up at 6am, Tuesday to Sunday, to work on the market. I sold hats with my grandma in a different town every day. I loved typing my sales on the big cashier and seeing the receipts come out. But the real magic of those days laid in the afternoons. Il panino della merenda was a ritual. Mum jokes about growing up with this huge American fridge, a sign of abundance in a kitchen from the 1970s. She jokes but also criticises the amount of fat she was raised on. That fridge was a mystery to me – it contained jars of a tradition that were my mother’s, but that weren’t in our kitchen. In the days when nonna was at the hairdresser’s or out shopping, I read on the balcony after playing in the garden, and then headed to the kitchen in the semi darkness, blinds down, sheltering the room from the heat of the day. I gazed at it, tall, black and white, double-sided. Fridge on the right, freezer on the left. And my favourite feature: an ice dispenser, a soothing relief for my pints of water. I ceremonially took prosciutto cotto or mortadella out of the butcher’s paper wraps, a piece of pecorino or caciotta, or even parmesan, lettuce leaves, and a big jar of mayo. I proceeded to layer all the ingredients in between two slices of fresh rustic bread, and took it back to the balcony to eat. I’ll never forget the day I found an unlabelled jar, its content, the colour of mayo, to only discover upon tasting that it was strutto, melted pig’s fat used for frying pastries such as frittelle and chiacchiere, the sweet treats of Carnival. I have since stopped adding mayo to my sandwiches.

There are seasonal dishes and flavours that roam in my head: seafood pasta for Sunday lunch in the summer, anolini in brodo in the winter, zia Maria Luisa’s fish soup soaking garlic croutons at the house in Antibes, dad walking in with fresh croissants and pains au chocolat every morning. I have never in life felt so purely happy as when I sat on that balcony, with a fuming mug of caffè latte, and a still warm pastry, my brother always by my side. We licked our fingers covered with the remains of French butter, while dad and zio Eugenio eyed each other over the newspapers. Same news, different ideologies. Their bickering made us laugh, especially when swearing was involved. The status quo resumed quickly, as one passed the pack of biscotte to the other, and the other looked at the jam jar’s label muttering: “This is good for you.”Mum and our cousins would pack the bags for the beach, while zia Maria Luisa would make sure we all had enough to eat and drink before sitting down with her cup of milk. I can return to those mornings, I can hear the seagulls, smell the neighbours’ lemons, feel the heat on my tanned skin.

My memories are filled with home-cooking. Restaurants were expensive, and considered unnecessary by my mother, whose inventiveness in the kitchen still amazes me. But among the fresh pasta and whole fish roasted in the oven, the simplest and best possible night was toastie night. We each picked our filling – ham, cheese, maybe some anchovies and tomatoes – before toasting each parcel of goodness. We ate them directly on kitchen rolls, longing for the slightly charred crust, and playing with strings of melted cheese.

There was one restaurant dish I obsessed over. I still think about it, and remember exactly how it was presented. It was cooked by chef Isa Mazzocchi at La Palta di Bilegno, the family restaurant where my parents hosted their wedding reception in 1991. Before it gained a Michelin star, national and international fame, it was the kitchen of a man and a woman, and later of that woman and their daughters. If there was a special occasion that’s where we’d celebrate it, and that’s where we celebrated my First Communion. I remember it all. The white gown, the wooden cross around my neck, the flower crown, the songs we learned to praise our Lord, the fear of tasting the corpus Christi for the first time, the shame of the first confession.

I had picked a white dress, tights, and a cardigan for the celebratory lunch, and I had been very specific in requesting my dish of choice as the main.

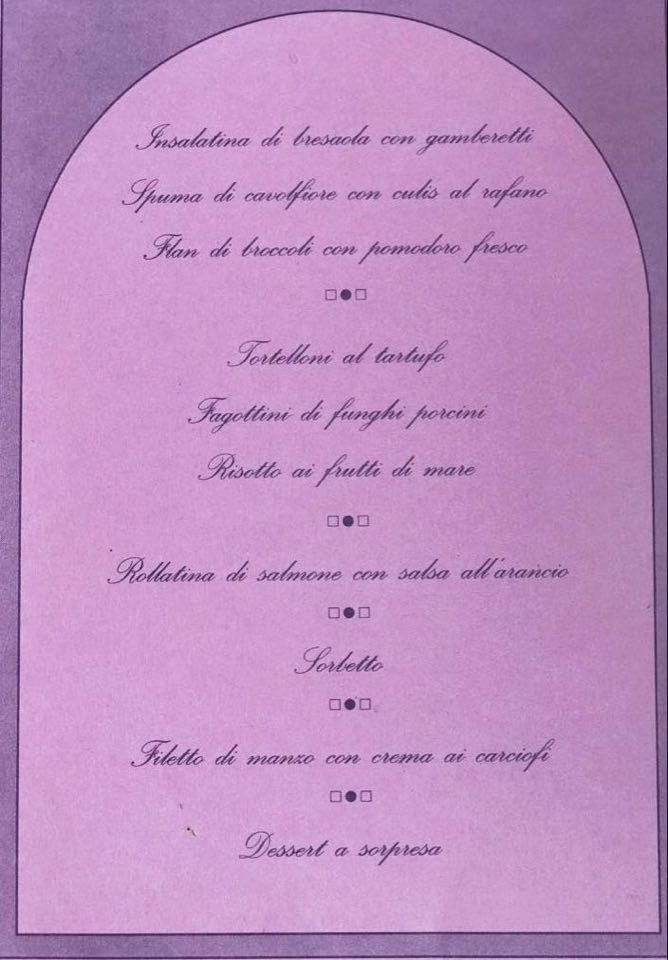

Fagottini di funghi porcini. I never had a recipe for these, but they were made of savoury crepes, filled with ground porcini mushrooms, ricotta, herbs, maybe a little truffle. The detail that stayed with me was the way they were closed like small wrapped gifts– tied together at the top with a stalk of chives. They were the most delicate things. There are photos of me roaming around the long sharing table, to each relative, telling them about the dish that was about to come, and that it was my favourite. After the antipasti, maybe out of the growing anxiety of being deemed culpable and responsible for my sins by the priest, or out of a simple childish mood, I started having awful stomach cramps, so bad I couldn’t eat anything at the table. I watched all the guests eat my parcels, and my mouth has been watering ever since. Last year, as my mother tidied old photographs, she stumbled upon hers and dad’s wedding album. In it, she found the original menus of the day, she didn’t remember keeping them. The second primo served were my, our, fagottini di funghi porcini.

Each of the foods in this childhood retelling is something I can still taste if I close my eyes. Food memories are a powerful tool of social understanding, of family and power dynamics, personality traits, and of being remembered for something. In my case, as the girl in pink, biting a piece of cheese.

Irene, May 2020