The first time I saw London I was a child, and London looked like a dream. Peter Pan held Wendy Darling’s hand and she held her brothers’, pixie dust lifted them outside a bay window in Bloomsbury and they flew out, turning into tiny shadows around the Big Ben. A sleepy city, enveloped in grey, unaware of the magic happening outside. Their silhouettes and the ultimate symbol of London are inked on my right foot, as a reminder that this city was my magical dream years and years before it became my reality.

I met the city again on screen and in books. There was Notting Hill and there was Bridget Jones, there was the Harry Potter saga, although the formative image etched in my mind was of Posh Spice driving the Spice Bus over an opening Tower Bridge in the incredible and mental film that is Spiceworld. There was Robin Williams forgetting he had once been Peter Pan and talking to an old and tired Wendy, remembering, looking at London from a top floor bay window, and flying back to Neverland.

My parents don’t remember a time in which I didn’t want to move to the U.K. It was an idea brewing in my childhood brain, a product of an imaginary ideal of what London was, of what the U.K. could be if I really lived there. Then came Jane Austen and Virginia Woolf, and I wanted to be a part of the world of these women, thinkers, writers, revolutionaries of their times. The music followed with my father blasting London Calling and the Guns of Brixton by The Clash in our car, while my mother obsessed over Lady D.

So, it was with nervous expectation that I boarded the first one-way flight of my life ten years ago, aged 19.

A decade on and it’s been a strange summer. The kitchen hasn’t always been the refuge it usually is for me. I reflect on time constantly, almost obsessively. I date every single blank page I work on: my Pages documents, work meetings notes, my journal, my messy notebooks, recipes, birthday cards, letters. Dates are the crumbs I leave behind to make sure I don’t forget. Losing my memory is the thing that terrifies me the most in life. As I turned 29 this past summer, everything felt heavy. I didn’t feel like celebrating, I didn’t feel like being reminded that ‘next year you will be 30 and then you’ll see,’ the sentence older friends and family members kept repeating to me all summer. Can someone feel old and yet so unprepared for adult life? Still, I know this birthday hit differently because it meant another anniversary was approaching. The realisation that I have lived in the U.K. for over a third of my life. London is my home, English is my language, and yet, post-Brexit Britain will always make me feel distant from the connection I felt with this country when I was 19. Home will always feel further away because of the barriers that have been put up between this island and the mainland that birthed so many of us.

I never paid taxes in Italy because I was never an adult in my birth country. I grew and matured in a different country from my entire family and my childhood friends. I write in English because it belongs to my everyday. I still write and speak Italian often, but it takes me much longer to elaborate sentences, and people back home tell me they hear an accent in the way I pronounce certain words. My voice goes up in tone when I speak English, it becomes gentler, I articulate words like in a theatre performance. My brain blanks sometimes and I can’t make sense in either language, so I sit in silence, waiting for a reboot. My voice gets more guttural, louder, faster and more confident as I speak Italian. Dialect, slang, swear words, of which I say many, roll out of my tongue almost in relief. I am home and nobody will ask me to repeat. ‘Where are you from?’ The waiter at the Pret near my office asks as I wait for my flat white. I pause for a second. Italy. Though I really want to say here, I’m here, this is where I am from. As this anniversary approached, I found myself following my past self’s steps across the city, tracing the perimeter of those first few months living at a pace that was unknown to me then. It thrilled me, and I wanted to see it all.

That winter, the Christmas lights on Regent’s Street recited the lyrics of the Twelve Days of Christmas, I wore a Primark faux-fur coat and it snowed. It was the perfect winter, we had our locals: Gaby’s, the Crown Cafe, the BFI Riverside bar before it turned all fancy.

In my mission to preserve time, I have been documenting my presence in this country obsessively. I can tell you where I walked the most each year as the perimeter of the city expanded in my mind and for my feet. I often wonder at what point London will stop working for me, for my body, for my brain that seems to grow more confused by the day.

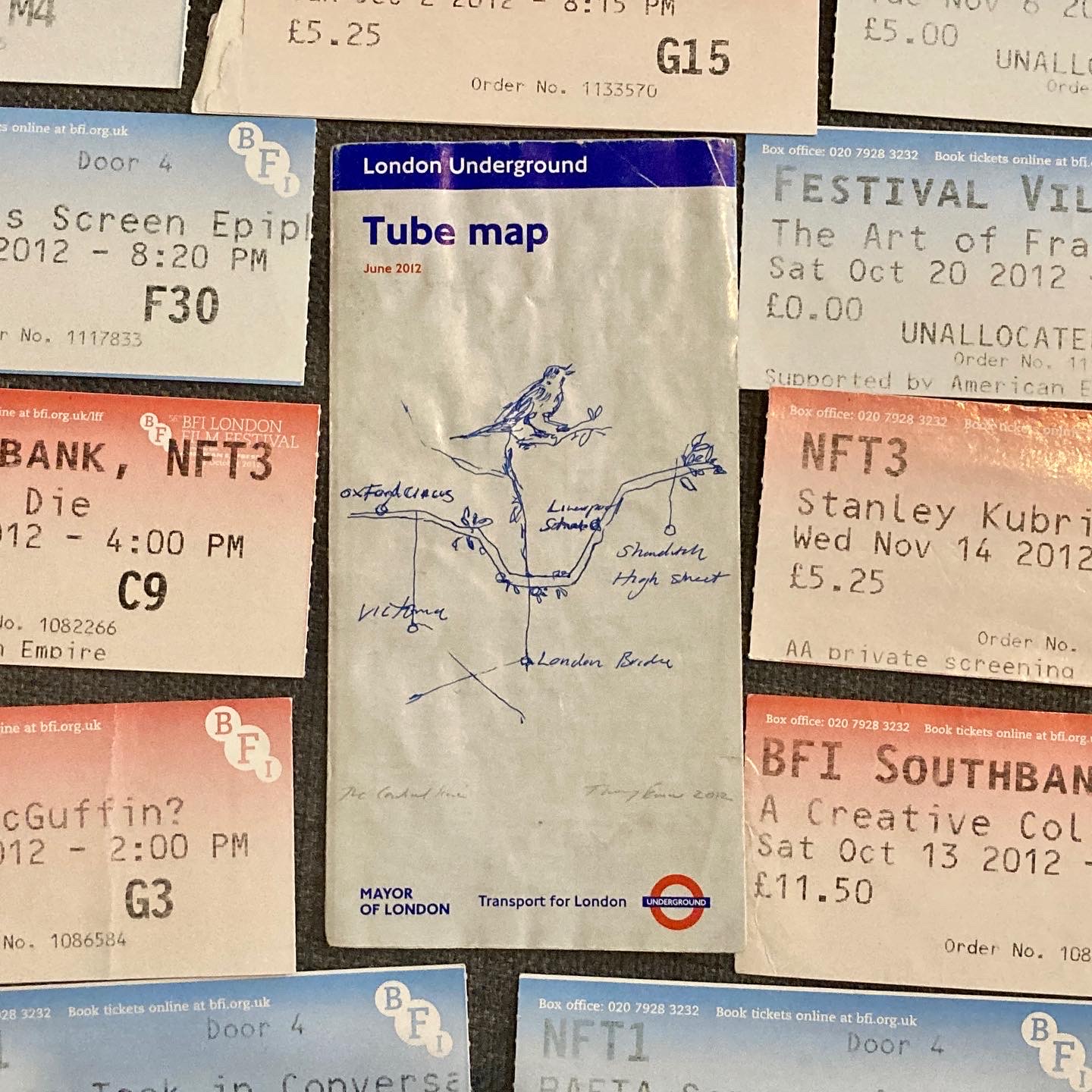

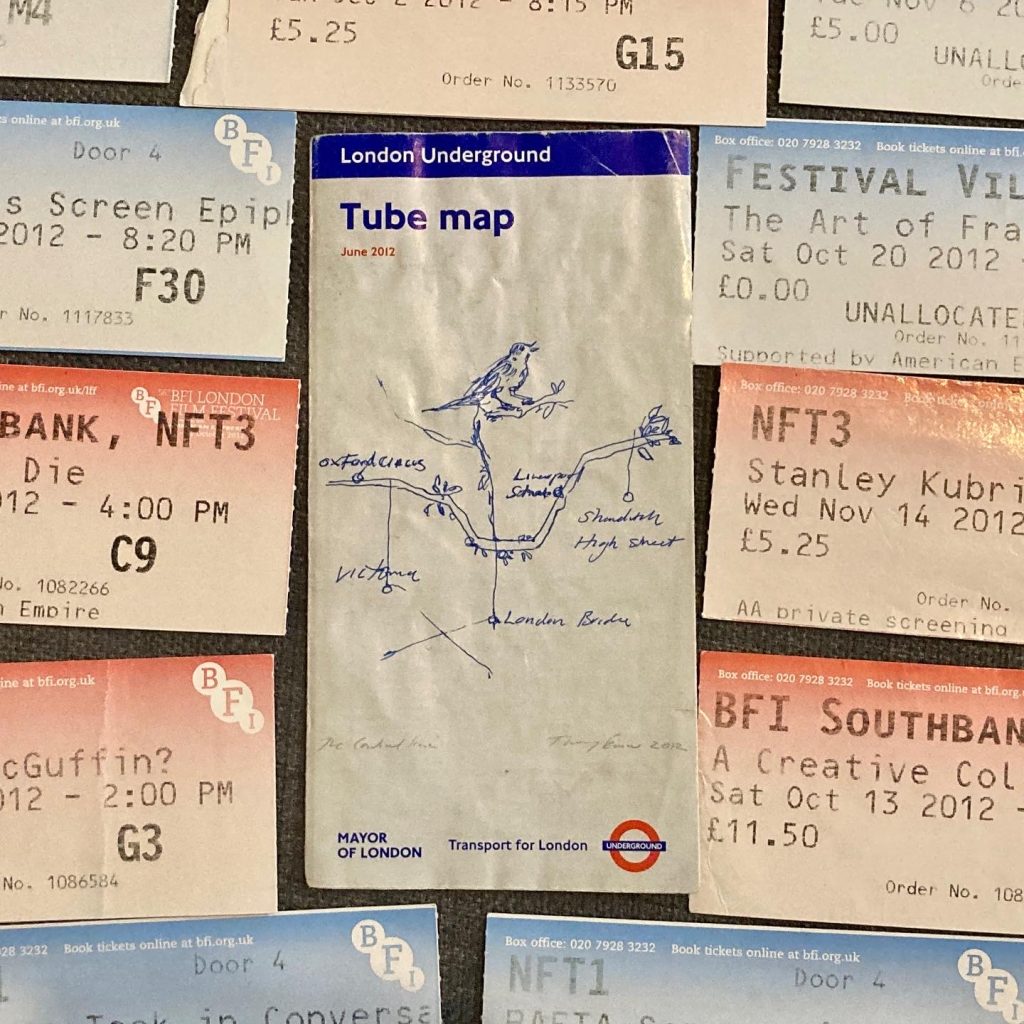

Leading up to this anniversary, I wanted to remember what those first few months here felt like, and so I opened my box of London, my crumbs of time, and amongst my settled status paperwork, bills, lease agreements and employment contracts, I found:

- My fuchsia iPod.

- King’s College London Freshers’ Week notepad filled with film scenes’ breakdown, abbreviated camera movements and timing of cuts in each scene, quick notes taken as we analysed films in the dark of the classroom.

- A list of films to get for my DVD library based on the films I was about to study at university.

- A gift envelope from my best friends with a letter from each. I opened and re-read all of them, and suddenly I was her again, myself at 19. My friends knew me well. They dated each letter, maybe they knew I’d keep them forever.

- One of my friends had added a blue pen to her letter noting I could use it to write about everything now I was going to study something I liked every day. I associated blue ink with my favourite subjects throughout school and black ink with the subjects I couldn’t follow, namely Maths.

- A London tube map dated June 2012, the summer of the Olympics.

- My cinema tickets from the first months in London, consuming film after film and event after event, thinking I was living in a bubble of silver screens and dark rooms.

It was strange to meet my younger self in the words of others. I do miss certain parts of myself that belonged to the young woman who had only ever lived in one place, one house, knowing each person on the street by name, surname, nickname and marital status. She smiled more. She also cared too much about other people’s opinion, but she danced on tables and genuinely loved it. She soaked in every bit of summer as if it was her last. She also took moments and things for granted. She was prone to heartbreak. Still, she followed her own rhythm and kept going. She started high school failing English and finished it with the offer to study at King’s College London. She’s gone. London gives and London takes. The city feeds on our insecurities, fears, and ideas of success. She wants us to keep going. But what if we want things to slow down? What if we are the ones deciding to slow down and not depending so much on what the city offers, which is in most ways how the city owns us?

There was one time in these 10 years where I almost left London. I keep thinking what would have happened if I had. I met my people right after and kept friendships that will now be turning 10 too. I would be writing a very different essay if I had left, maybe I wouldn’t be writing at all. I am grateful to my father for convincing me to stay. Life became wonderful and miraculous and even all the changes of direction and changes in dreams felt right, they felt like they were happening for a reason and that I would have always found a way to keep myself afloat amidst the anxiety.

More importantly, the U.K. has given me a food revolution. And maybe this is why I came here in the first place, to taste things that were new to me. I have eaten the city voraciously. I noted my favourite foods by mood, my favourite places to return to my country through a dish, the recipes I wanted to recreate at home. My food shopping became more adventurous, and I now use ingredients I didn’t even know existed ten years ago as a staple in my everyday cooking. I cook fish heads and livers, I blend prawn heads and use their juices for seasoning, I save roast chicken bones and drink their generous, oily broth, I use miso in my tomato sauce, I make risotto through all the colours of the year, I can make bread, I can juggle multiple pots on a tiny kitchen hob. I steam frozen dumplings and boil water for instant noodles, I make flour mountains and crack eggs in them as orange as sunsets, I melt vintage Cheddar in cheese toasties and spice it with all sorts of jams and chutneys. I make ragu from scratch in my green casserole, I use more butter in my cooking than I used to, I make vegan béchamel that is creamy and glossy all the same, I grate nutmeg with a tiny grater trying not to grate my fingers with it, I drink gin tonic, I watch Love Island in the summer and voraciously follow Twitter updates, I complain about my neighbours, I try to keep plants of basil alive, and fail at it, I drink tap water only, I have to remember bread comes at an extra cost when I order more. I eat fish and chips but always end up being full before I finish it, I live for glossy prawn wontons in chilli oil and I can dip most things in mayonnaise or aioli. I search for coppa in Italian delis and order 100g to take home and eat wrapped around breadsticks. Pubs give me joy, I forgot how to drive, but I like walking everywhere. A quiet tube journey is always great, a busy and sweaty one will always be miserable. I will always pace faster if I’m passing by the M&Ms store in Leicester Square. Friday nights are for the theatre. Brunch is actually not that great. Eggs and soldiers are a most excellent breakfast. I don’t want a meal deal, I will keep eating pasta for my lunch even if others tell me it’s too heavy. I speak loudly in my Italian accent, I don’t want to lose it. I want to vote, but I can’t afford to apply for citizenship yet. I can’t vote, but my taxes have gone up and I am more tired in the evenings. The journey to and from Stansted Airport always exhausts me. I will not tolerate chicken on pizza or in my pasta, and I’m not sorry for it. My name is Irene Olivo, not Airin Olivio, or Airine, or Aireen or Irena. I will keep pronouncing words wrongly and using wrong terms, and not composing perfectly structured sentences. I love it here and I hate it here, and then it takes one romantic afternoon between myself and this city to forgive, it takes one look at the symbols of my childhood dreams to forget and see everything exactly as it was that September, 10 years ago, London waiting just outside my window on Stamford Street, stretching wider, postcode after postcode, house after house. I was just a girl, looking out her window, hoping life could feel that perfect forever. (Pardon my butchering of Notting Hill’s iconic line).

Despite all the nostalgia and romanticism in the world, the relationship I had with London and the U.K. has felt increasingly tarnished over the past few years. Brexit, the changes of direction so many of us have had to accept after university, rejections and rejections piling up in mailboxes, heartbreak, mice creeping into our households, water leaks, broken windows, rent increases, angry landlords, greedy agencies, favourite places closing down pushed out by ridiculous rents, Grenfell, the U.K.’s treatment of refugees, police brutality, the rubbish piling up on the streets in a city that keeps consuming, a race to achieve, to get promotions, to earn more, to burn out faster, mental illness, panic in the tube carriage, attacks in London Bridge, the pandemic, 100,000 dead, and counting, the NHS crumbling, Jubilee celebrations while we can’t afford bills and a funeral for taxpayers to pay while the royal family dances on privilege. And, in between, life. Sunsets over London bridges, friendships found and claimed as our own, love, kissing, dancing in loud and sticky ballrooms, live music, new foods entering our vocabulary, dinner parties, walks in parks, train rides to escape the mess for a weekend, rides to the airports connecting us to our home countries, languages, families, however we recognise them to be.

I want to stroll through parks and follow the deer more than I want to walk on the hellish stretch that Oxford Circus is today. I want to stop in small shops and chat to the owners instead of seeing a string of American candy stores popping up everywhere I look. But I also want to be able to save and not spend all my money in said shops, sometime for the sake of a home memory. I want markets that are affordable and accessible and where people can chat to producers and understand about what we put on our plates. I want a city that feels safe to walk home in, despite my fear of the darkness, keys clenched between my fingers. I don’t want to depend on whatever pattern we have set for work in order to live. I don’t want to gasp for air at the end of the week, I want to breathe every day.

So why do I stay? Some days it gets very difficult to answer this, while others it’s the simple answer it would have been 10 years ago. Because this is home. As simplistic as this might sound, London is the first place that has felt like home to me. A home I had chosen, people and a family I had chosen and that thanks to my lucky star had chosen me in return.

The U.K. has made me a walker, through parks and backstreets, high streets and riversides, on pebbly beached and then resting on benches dedicated to someone’s memory. London wears its history on a sleeve, and yet it forgets it. The school system still confuses me. The cost of living is becoming more unbearable by the day and we stay home to save. A silent domestic revolution.

This is the country where I marched and joined a Union. This is the country where I developed my political consciousness and where I find myself unafraid to speak up. London is where I moved 8 different houses, and gained over 30 flatmates. It’s where I had to prove my right to work.

Living away from Italy for a decade has also taught me how to miss my home country. It has, ironically, shaped me more as an Italian woman. I will never forget the beginning of the Covid pandemic in Italy, as the virus spread around the corner from my town, my whole family suddenly staying home and being terrified as people started dropping dead around them and the sound of the ambulances filled the empty streets. I remember this country’s indifference and my physical need to return to Italy, as my stomach knotted with each passing day that our government decided to ignore our reality. I sobbed in rage as Boris Johnson said we would need to get used to the idea of losing loved ones. The elderly, who in Italy are considered pillars of collective history and memory, were suddenly disposable here. Vulnerability was a flaw and people were numbers, rising daily. I return to Italy any time I can since travelling restrictions have been lifted, I feel closer to it than I ever did when I lived there. I imagine a future there too, despite all its complications. I still imagine a future in the U.K. too, and so I allow myself to dream up possibilities and lives for myself once more.

I walk through London as I exchange vocal messages with my Italian friends and family. I tell them where I’m walking to, names of restaurants, parks, people I am meeting they have never met. They hear the sounds of the city in the background of my voice. I listen to them as they drive the familiar streets of our towns, as they tell me about town characters and latest local adventures. I make a mental note of places I want to go to with them when I visit next. I keep walking and talking at the same time. Minutes and minutes of these snippets of life recorded as I cross bridges and streets, as my train is delayed, as I get anxious in a packed station. The voices keep me company when I walk alone, they remind me of where I am from, but also about where I am going. I often mention the things I say in these messages in therapy. I find home in my friends’ voices and I find new homes in my friends’ houses in London. We set the table and simmer dinner, we sit by windows and cheer to whatever that week has brought. We return home content and on night tubes, observing how our fellow commuters have spent their evening. There is always a drunken group, there’s always someone eating a sandwich, there are often dogs and babies, elderly people travelling with their families after the theatre, students who have just arrived in London.

I observe them the most. With their newly-formed friendships, rooms with tiny bathrooms waiting for them in student halls, nights out that feel like the best nights out in their lives, London’s sights still feeling new and miraculous. I won’t break their spell.

I get off at my stop. I am home.

Irene, September 2022